Animales Domésticos en el Proceso Colonizador del Siglo XVII

Animales Domésticos en el Proceso Colonizador Americano del Siglo XVII

This study presents colonial American history as the story of three-way interactions among Indians, English colonists, and livestock. By situating domestic animals at the heart of the colonizing process in 17th-century New England and the Chesapeake region, the book restores contingency to a narrative too often dominated by human actors alone. Livestock were a central factor in the cultural clash between colonists and Indians as well as a driving force in expansion west. By bringing livestock across the Atlantic, colonists assumed that they provided the means to realize America's potential, a goal that Indians, lacking domestic animals, had failed to accomplish. They also assumed that Native Americans who learned to keep livestock would advance along the path toward civility and Christianity. But colonists failed to anticipate that their animals would generate friction with Indians as native peoples constantly encountered free-ranging livestock often trespassing in their cornfields. Moreover, concerned about feeding their growing populations and committed to a style of animal husbandry that required far more space than they had expected, colonists eventually saw no alternative but to displace Indians and appropriate their land. This created tensions that reached boiling point with King Philip's War and Bacon's Rebellion, and it established a pattern that would repeat time and again over the next two centuries.

Keywords: colonial American history, Indians, Native Americans, English colonists, New England, Chesapeake, livestock, animal husbandry, King Philip's War, Bacon's Rebellion

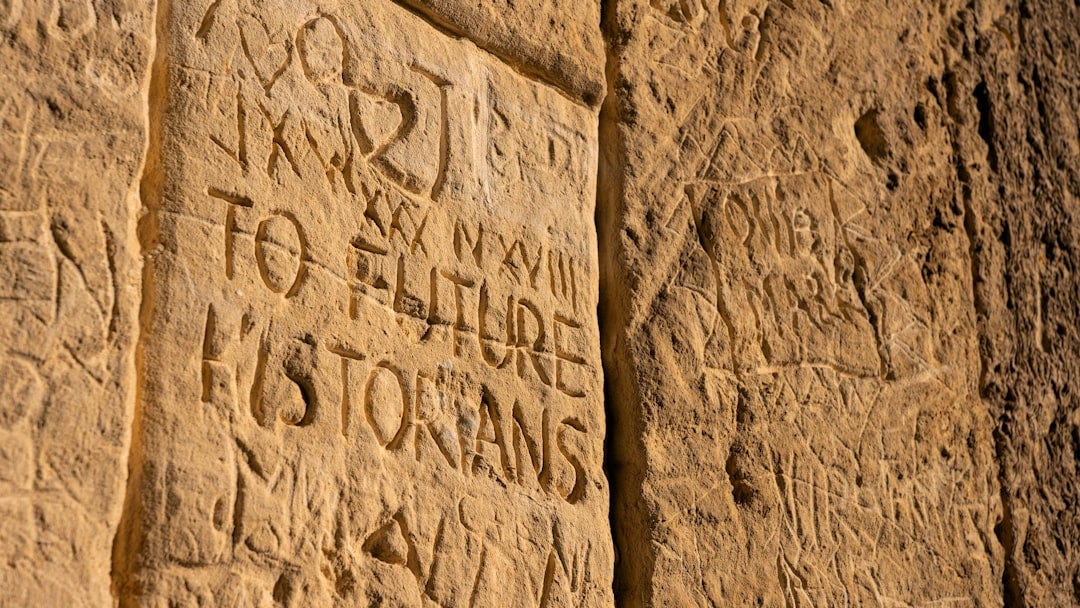

One of the oddest historical markers in all of New England can be found in the town of Duxbury, Massachusetts. A simple granite slab, it stands about five feet high and is perhaps two and a half feet wide. It was erected in 1940, shortly after Duxbury citizens observed the tercentenary of their town's founding. Yet the monument does not commemorate Duxbury's beginnings. Nor does it celebrate the achievements of a local notable, note the location of an historic building, or commemorate a battle. The marker instead shows where a fence once stood. Carved into its granite surface are the words: “SITE OF NOOK GATE. HERE A PALISADE WAS ERECTED ACROSS THE NOOK IN 1634. THIS PALISADE WAS A HIGH FENCE TO PREVENT CATTLE FROM STRAYING AND PROBABLY TO KEEP THE INDIANS OUT.”

The inscription recalls the familiar proverb about good fences making good neighbors, and yet at the same time it conjures up an unlikely image. The neighbors involved here—Indians, cattle, and (by implication) colonists—are not the typical cast of characters featured in New England histories, let alone on granite monuments. Colonists, of course, appear in force both in histories and on markers, although their fence-building efforts are seldom memorialized. Indians, still scarce on monuments, are at last achieving something like parity in written accounts of New England's past. But cattle? Livestock seldom figure at all in the narrative of colonization, and when they do they usually serve as part of the scenery rather than as historical (p.2)

Prologue: Seeing Banquo's Ghost Marker for Nook Gate, Duxbury Massachusetts. Photograph courtesy of Juan De Zengotita, in author's possession

actors. The Duxbury marker may be the only monument to mention their presence in all of New England. If only one such memorial had to exist, there would be no better place for it than Duxbury. For all intents and purposes, cattle determined when and where the town would be established. Settlers in nearby Plymouth first broached the subject of creating a new community as early as 1632, once they noticed their proliferating herds overtaxing the local supply of pasture. Several miles up the coast anxious farmers found the open meadows they needed. First a trickle, then a small stream of families made their way with livestock and other belongings to the site of what eventually became Duxbury.1 The fence that these farmers built in 1634 to protect their animals (p.3) was most likely a makeshift post-and-rail barricade rather than a sturdy “palisade.” It almost certainly failed to keep cattle from straying. During the seventeenth century, New Englanders frequently drove livestock to “nooks” or small peninsulas and tried to confine them by fencing off the narrow entryway. They trusted, often in vain, that the animals would not swim around the barrier.

It is equally unlikely that the fence kept “the Indians out,” or was even meant to do so. Colonists in this part of New England, at least during the 1630s, were not in the habit of keeping their distance from Indians. English settlers traded with local Wampanoags, hired their labor, and encountered them often in town and in the woods. Plymouth colonists and Wampanoags had formed a military and diplomatic alliance. While it would be going too far to suggest that the two groups delighted in each other's company, they were not necessarily antagonists. That unfortunate relationship would come soon enough, but discord did not characterize their encounters as early as 1634. Like neighbors everywhere, Indians and colonists were learning how to get along with one another.2

The inscription on Duxbury's monument may not be accurate in every particular, but by linking the experiences of Indians, colonists, and cattle it speaks to a larger truth. Historical narratives usually attribute the course of events to the conscious decisions of human actors, yet this is not always the way in which history itself unfolded. Sometimes other kinds of actors were involved, driven by instinct rather than reason. Such was the case in seventeenth-century America, where the lives of Indians and colonists alike were often shaped in unexpected ways by the activities of animals. This book, by incorporating livestock into the history of early America, restores an important element of contingency to the narrative, making it less familiar but no less compelling. It argues that leaving livestock out of the story of early American history is a little like staging Macbeth without the scenes in which Banquo's ghost appears. The ghost has no speaking role, but it is nevertheless central to the plot. The same point applies to the part played by livestock in the era of English colonization.

Unlike Banquo's ghost, however, livestock appear in almost every scene. Virtually every body of sources pertaining to seventeenth-century English colonization, from local records to descriptive pamphlets to treaties with Indians, mentions these creatures, often with astonishing frequency. If the sheer number of references in the historical record offered an accurate (p.4) measure of a topic's significance, one could easily argue that a history of livestock in colonial America is long overdue. But the interpretative challenge of such a project lies in assembling countless documentary fragments into a story that makes a case for the animals' importance, not just their ubiquity. The likely outcome would be less a history of livestock than a history of people with livestock in it.

Creatures of Empire began as an effort to understand why references to livestock appeared so often in documents related to early American history and how paying attention to those references might affect our understanding of the process of colonization. Like the Duxbury memorial, the book introduces three sets of actors: livestock, Indians, and colonists. In contrast to the point of the monument's inscription, however, the book argues that these people and animals shaped the course of colonial history because of their interactions, not their separation from one another. Its story is set not just in New England, but also in the Chesapeake colonies of Virginia and Maryland during the seventeenth century, an era when the most profound encounters occurred and when patterns of behavior emerged that would influence the conduct of generations to come. The regional comparison amplifies the significance of the narrative, for its central findings cannot be characterized as peculiar to only one group of colonists. By following developments in New England and the Chesapeake, the book reveals how a common English background was refracted into distinct colonial experiences that, despite manifest differences, ultimately converged to reach the same bitter end.

This is by no means the first history to posit that animals can play an important role in human affairs. For several decades, environmental historians have taken animals seriously as agents of historical change, particularly in the era of European exploration and expansion. Beginning with the seminal work of Alfred Crosby, numerous studies have accorded livestock an instrumental role in helping Europeans to establish colonies in other parts of the world. Especially in North and South America, the success of those imperial endeavors depended on the migrations of people and animals.3

Central to many of these narratives is an examination of the ways in which livestock helped to reconfigure New World environments to suit European purposes. By competing with local fauna, clearing away underbrush, and converting native grasses into marketable meat, imported animals assisted in the transformation of forests into farmland. These (p.5) changes alone sufficed to disrupt the lives of native peoples; by contributing to erosion, altering microclimates, and introducing other ecological shifts, livestock compounded the difficulties that Indians faced after colonization began. Environmental histories thus bring Indians, colonists, and cattle together as participants in a common story, but they do so in a distinctive fashion. Because livestock tend to be discussed in terms of the ecological alterations they produced, the effects of their presence on people are largely indirect, mediated by the environment itself.

This book necessarily incorporates the important findings of such studies, but moves the story in a new direction by exploring direct interactions between humans and livestock. It argues that the animals not only produced changes in the land but also in the hearts and minds and behavior of the peoples who dealt with them. And sooner or later, everyone—Indians and colonists—had to deal with livestock. Despite their status as domesticated creatures, the animals were never wholly under human control. Sometimes they acted in ways that their owners neither predicted nor desired, provoking responses that ran the gamut from apology to aggression. To a remarkable extent, the reactions of Indians and colonists to problems created by livestock became a reliable indicator of the tenor of their relations with one another.

In its insistence that Indian peoples were active participants in the story of colonization, this book draws upon a wealth of recent scholarship that has emphasized precisely this point.4 Such work places intercultural encounters securely at the center of early American history. Just because the historical record is tipped heavily in favor of the colonists, Indians cannot be relegated to supporting roles. Inspired by their own vision of what a colonized America could be, Indians took the initiative as often as the English did to try to shape the world in which they all lived. If disparities in the documentary record pose one obstacle to a full appreciation of Indians' efforts, an equally formidable problem emerges merely from knowing from the outset how the story will end. No account of Anglo-Indian relations in early America can avoid acknowledging that the English ultimately predominated. Constructing the story to reach that end as directly as possible, however, risks converting a tragedy into a melodrama. Such a narrative strategy ignores the actors' attempts to explore alternatives that did not succeed and fails to ask why events turned out as they did. Perhaps the greatest challenge in composing Creatures of Empire lay not in reconstructing what did happen but in imagining what might have been. The conclusion of this book may surprise (p.6) few readers, but the path it takes to reach that end is anything but direct or predictable.

Since English colonists—unlike livestock and Indians—have always been regarded as key historical actors, it may seem superfluous to reiterate the point here. But colonists have typically been portrayed in their roles as town founders, magistrates, preachers, soldiers, and even parents. Only rarely do they appear as farmers, the role that occupied more of their time and energy than any other. This was the reason why they brought livestock to the New World in the first place, however, and thus it is central to this story. How they farmed turns out to be particularly important, for agricultural practices largely determined the circumstances under which Indians, colonists, and cattle encountered one another. Indians farmed too, but did so without domestic animals—a difference that turned out to be far more significant than anyone could have imagined.

Agriculture has never been exclusively an economic activity, but has always reflected cultural assumptions distinctive to particular groups of farmers.5 Colonial America was no exception in this regard. Although Indians and colonists both farmed, their agricultural activities were embedded in quite different cultural contexts. Indians and colonists did not agree on whether men or women should till the land, how to define property rights, or how humans ought to interact with animals and the natural world in general—all issues that related to agriculture but had broader implications as well. Colonization, by bringing these two sets of assumptions into contact, produced changes in both. Within a few short years, Indians and colonists neither farmed nor thought about animals and farming in quite the same way as they had done before they became neighbors.

Further complicating matters, the English characterized their own livestock-based farming methods as “improvement” and incorporated this notion into their imperial designs. Introducing Indians to civilized ways (which included livestock husbandry) became a principal goal of colonization, and colonial farmers were to help achieve this result through the strength of their example. Such a plan required both the appropriation of land for colonists' farms and the transformation of native villages to make them accord with English models. That transformation failed to occur to the extent that colonists wished, but the appropriation of land proceeded apace. Before long, the expansion of livestock-based agriculture ceased being a model for Indian improvement and instead served almost exclusively as a pretext for (p.7) conquest, a very different expression of the cultural impact of distinct farming practices.

The significance of the narrative that follows is paradoxically rooted in its preoccupation with details of life so ordinary that they have rarely been considered the stuff of history. Books about colonization in early America more typically dwell on themes of politics, trade, religion, demography, and warfare. Without discounting the importance of these topics (for each has a place here) and with no intention of offering a monocausal explanation for complex events, this book argues that sometimes mundane decisions about how to feed pigs or whether or not to build a fence also could affect the course of history. Three groups comprise the cast of characters. The first is the Algonquian-speaking Indian peoples who lived in the New England and eastern Chesapeake regions. Although this language group in fact comprised dozens of separate bands occupying lands stretching from present-day Nova Scotia to North Carolina, as members of the same linguistic family Algonquian speakers descended from common ancestors and shared cultural characteristics. The other two groups are the English colonists who arrived during the seventeenth century, and the livestock they brought with them to the New World. The book's plot traces their complex interactions as the two immigrant groups attempted to make a place for themselves in America and the Indians tried to retain some hold on the places that had always been theirs. As events turned out, livestock—the one set of characters incapable of making plans—proved fully capable of upsetting the plans of all of the people around them.

Because how people think about animals influences how they interact with them, the book begins with a pair of chapters that explore Indian and English approaches to nonhuman creatures. The comparison reveals that, although the two ways of thinking were not utterly distinct, the differences between them were significant enough to complicate the myriad encounters between Indians and colonists that involved animals. Native understandings of animals fit into a larger set of conceptions about the world that drew no sharp boundary between natural and supernatural realms and did not dictate the subordination of nonhuman creatures. Some animals possessed spiritual power, obliging the humans who hunted or otherwise dealt with them to show respect. Indians thus conceived of their relationship with animals in terms of balance and reciprocity, not domination, let alone ownership. But (p.8) these ideas about animals, derived in good part from the Indians' experience with wild creatures, ran counter to the views of English settlers whose principal contact was with domesticated beasts. Christian orthodoxy affirmed the colonists' practical experience of dominion over animals that, in the case of livestock, was further reinforced by the animals' legal status as property. For Indians and colonists alike, encounters with new sorts of animals—whether English livestock or New World fauna—tested longstanding habits of thought. That members of both groups initially placed strange creatures into familiar conceptual categories was hardly surprising; whether they would be willing over time to adjust their views to accommodate alternative ways of thinking emerges as one of the main themes of this book.

The three chapters that make up the book's second section move the narrative from the realm of thought to questions of practice. Since England's experience with livestock husbandry was so widespread and stretched so far back in time, inhabitants could not help but see it as normative. Thus when proponents of overseas colonization argued in favor of an agricultural foundation for the new settlements, they implicitly included livestock husbandry as an integral part of the package. In so doing, they formulated plans that encompassed not only the introduction of an English-style agrarian regime but also the imposition of English cultural expectations. Raising livestock was not simply a way to make a living. Ideally animal husbandry inculcated a set of behaviors, all directed toward the efficient exercise of human dominion over lesser creatures, that manifested—at least in their own eyes—the colonists' cultural superiority.

Assumptions about animal husbandry insinuated themselves into England's imperial ideology in subtle ways and influenced much more than agricultural practice itself. Expressing an opinion based on their English experience, colonists asserted that farming with animals was one important hallmark of a civilized society. They claimed that using domestic animals to improve the land helped to legitimize English rights to New World territory. By bringing livestock across the Atlantic, colonists believed that they provided the means to realize America's potential, pursuing a goal that Indians who lacked domestic animals had failed to accomplish. English settlers employed assumptions about the cultural advantages associated with animal husbandry to construct a standard against which to measure the deficiencies they detected in native societies and to prescribe a remedy for their amelioration. Indians who learned how to keep livestock, colonists asserted, (p.9) would grow in prosperity, advance along the path toward civility, and eventually convert to a Christian faith that considered human dominion over animals to be divinely ordained.

Colonists who extolled the benefits of animal husbandry, whether to defend English claims to New World territory or to exhort Indians to change their ways, made one critical—and, as it turned out, erroneous—assumption. They took it for granted that they would be able to manage their livestock with the same care and attention that they were accustomed to using in England, thereby demonstrating the qualities of stewardship that made animal husbandry a civilized endeavor in the first place. But colonists had no idea how fully their energies would be absorbed in clearing land, planting crops (especially tobacco in the Chesapeake), building houses, and working at all the other tasks necessary to establish new towns and plantations. With scarcely any time or labor to spare for their animals, they had to let livestock take care of themselves. This highly attenuated free-range style of husbandry (which operated year-round in the Chesapeake and seasonally in New England) undermined the colonists' assertions about this aspect of their own civility even as it presented neighboring Indians with a whole set of problems that lacked easy answers.

The colonists' free-range husbandry guaranteed that Indians would encounter livestock at almost every turn, not just in English settlements but also along the shoreline, in the woods, and in their own cornfields. More often than not, those encounters resulted in damage to Indian property, to the offending creatures, or to both. To prevent minor disputes from escalating into major altercations, Indians and colonists spent considerable time and effort trying to figure out what to do with animals no one could really control. The significance of negotiations about livestock, however, extended far beyond the immediate problems they tried to address. The two chapters comprising the final section of the book argue that Indians and colonists used such deliberations to put forth competing visions of what a colonial society should look like. The fates of animals may have been the ostensible reason for negotiation, but the fates of people hung in the balance.

In other times and in other places, Indians and colonists managed to reach mutually acceptable solutions to their problems on a neutral “middle ground” occupied by both groups but controlled by neither.6 This was not the case in the Chesapeake or New England, two regions where colonists assumed a dominant position fairly quickly. Creative solutions demanded flexibility from (p.10) both sides, but in the places examined here, Indians proved far more willing than colonists to adjust their ideas and practices to accommodate the changes that livestock introduced to their world. For the most part, colonists restricted their cooperative efforts to showing Indians how to behave like the English. Yet ironically, the more Indians learned how to build fences or make other concessions, the less satisfied the colonists were with the results. Strengthened by demographic advantage, colonists' intransigence only increased over time. By the third quarter of the seventeenth century, changes that Indians had adopted as parts of a broader strategy for survival struck colonists as unwelcome obstacles to English territorial expansion.

Anxiety clearly contributed to the colonists' stance. Concerned about feeding their growing populations and committed to a style of husbandry that required far more space than they had anticipated, colonists could see no alternative but to appropriate Indian land. They often encouraged livestock to initiate the process by letting them move onto Indian territory prior to formal English acquisition. Native objections to these incursions met with little sympathy. As a result, colonists ensured that their animal property would become frequent targets of Indians' retaliation. By the time that simmering tensions reached the boiling point with King Philip's War in New England and Bacon's Rebellion in Virginia, livestock were sure to be implicated as causes, and to suffer as victims, of humans' unresolved differences.

After these deadly conflicts, victorious colonists saw no reason to change their ways and defeated Indians lacked the power to press the point. Colonial farmers exercised greater supervision over livestock only when they could marshal sufficient labor to do so. In the Chesapeake, improvements in animal husbandry awaited the arrival of substantial numbers of African slaves during the eighteenth century. In New England, reliant upon a home-grown rather than an imported labor force, the transition was even longer in coming: not until the nineteenth century did most farmers begin keeping close track of their livestock. By this point there were few Indians left in either region, and fewer still with their own land, to benefit from the new agricultural regimes.

Yet if livestock had been instrumental in dislodging Indians from their lands during the seventeenth century, the creatures also kept colonists on the move. Time and again, English and other European settlers reenacted their predecessors' experience in seeking new territory on which to support proliferating herds. Moving into Indian country and establishing settlements (p.11) where free-range husbandry once again prevailed, they set the stage for the same sorts of encounters among Indians, colonists, and animals that had occurred many times before in other places. Creatures of Empire is thus not so much a tale strictly bounded by time and place as an archetypal story of colonization and westward expansion. Like the first English colonists, subsequent waves of settlers and their American descendants declared that livestock would improve the land and its native inhabitants, but then deployed the animals to displace the Indians. Once the multiplying creatures overran a tract of land, the process began anew. As the advance guard and a primary motive for this relentless expansion, livestock deserve a place in the narrative of American history. In a real sense these creatures, even more than the colonists who brought them, won the race to claim America as their own.